Explaining technology history by Sugar - Deutsches Technikmuseum

Visiting technology museums in various places has always been a customary practice during my travels, and the Deutsches Technikmuseum mentioned in the text is no exception. However, this visit to an exhibition on sugar unexpectedly became the primer for my determination to start a blog website.

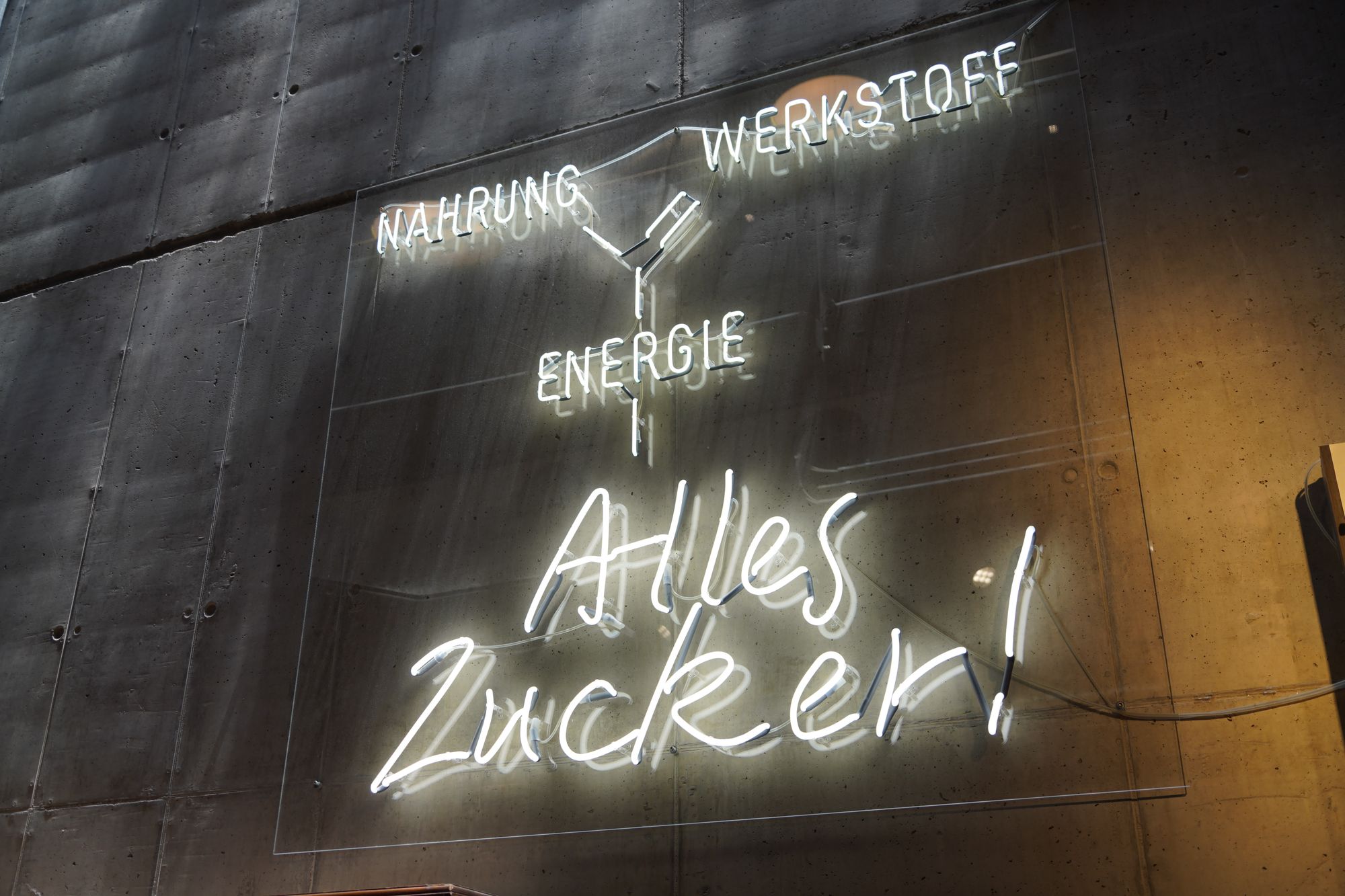

Sugar, also known as the collective term for polyhydroxy aldehydes and polyhydroxy ketones, is an essential component in our daily lives. However, choosing it as the central theme for an entire exhibition is a highly challenging task. After all, it is merely a food ingredient that some people even tend to avoid today. Nevertheless, through sugar as a medium, we are able to connect the technological history and political circumstances spanning several centuries, resulting in a captivating story.

Five hundred years ago, sugar was a luxury item. Its scarcity is difficult to comprehend for people today: even if we find the retail price of sugar at that time and adjust it for purchasing power, the value remains abstract. Museums, however, serve as places to narrate the past through objects. So instead of focusing on refined sugar, highlighting the containers used for storing sugar reflects its value.

A sugar container, made of silver and sometimes equipped with a lock, was even widely used as part of a dowry in those times, emphasizing its value. As a Chinese, I am pretty surprised to see the word dowry shown in this context.

The first transformation in the production of sugar occurred through the triangular trade. While sugarcane originally originated in the Old World, its widespread commercial cultivation took place in the Caribbean region. Although sugarcane is a tropical crop that requires sunlight and higher temperatures for growth, the most crucial production factor was human labor. Initially, it involved African slaves in the triangular trade. After the abolition of slavery in the 1830s, limited-term indentured laborers from India, China, and Southeast Asia were brought in to fill the gap.

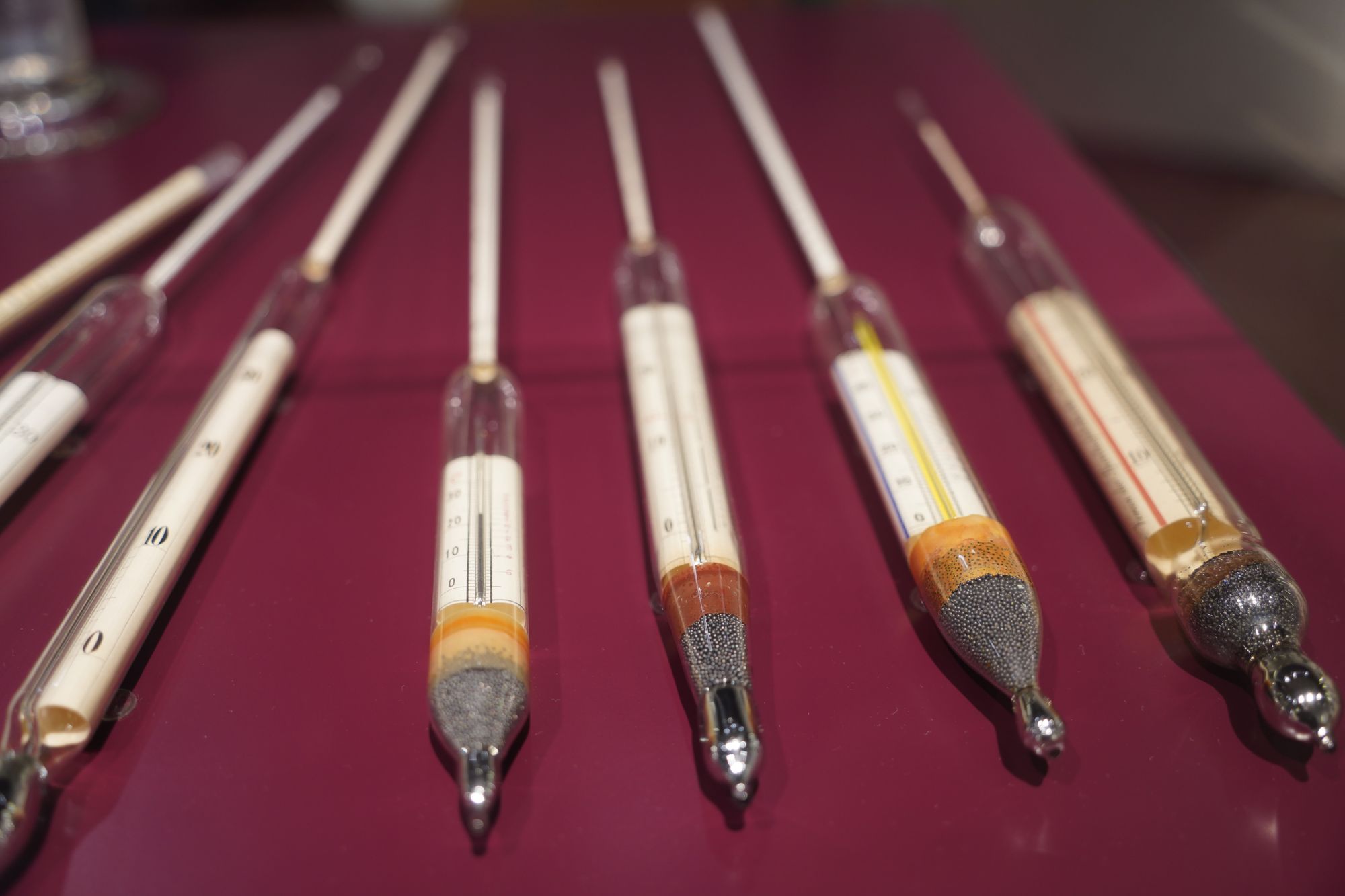

As a latecomer without colonies in the Caribbean, Germany did not have the opportunity to participate in the sugarcane industry chain dominated by France. The 18th and 19th centuries were the peak of mercantilism. The invention of sugar beets can be seen as a result of import substitution strategies. As the country that invented and majorly cultivated sugar beets, Germany naturally had a well-established system for industrial production of sugar beets. The exhibition includes abundant content on production processes, mechanization of cultivation, and standardization for beet sugar, with highly specialized instruments.

Although sugar beets were closer to the consumption market and had made more progress in agricultural mechanization, and also enjoyed state endorsement such as tariff against imported sugar, they never replaced the dominant position of sugarcane sugar in terms of global production. The competition between sugar beets and sugarcane sugar can also be seen as a competition between agricultural industrialization and agricultural outsourcing. In Germany, the production of sugar beets offered options not only for small farms but also for seasonal workers and factory workers. Compared to slaves or indentured laborers in the Caribbean, they had more freedom and could earn higher wages. Offshore production with no concern for workers naturally led to slower progress in mechanization. However, in industries where mechanization and automation only provide limited advantages, the increase in onshore productivity brought about by technological innovation cannot compete with wage differentials. You could have the full cost advantage of globalization, at the cost of unreliable supply chain, and maybe even social instability. As we navigate the turmoil of COVID and supply chain realignment, the sugar history is becoming more relevant.

Let's return to the lighter topic and take a look at the exhibits.

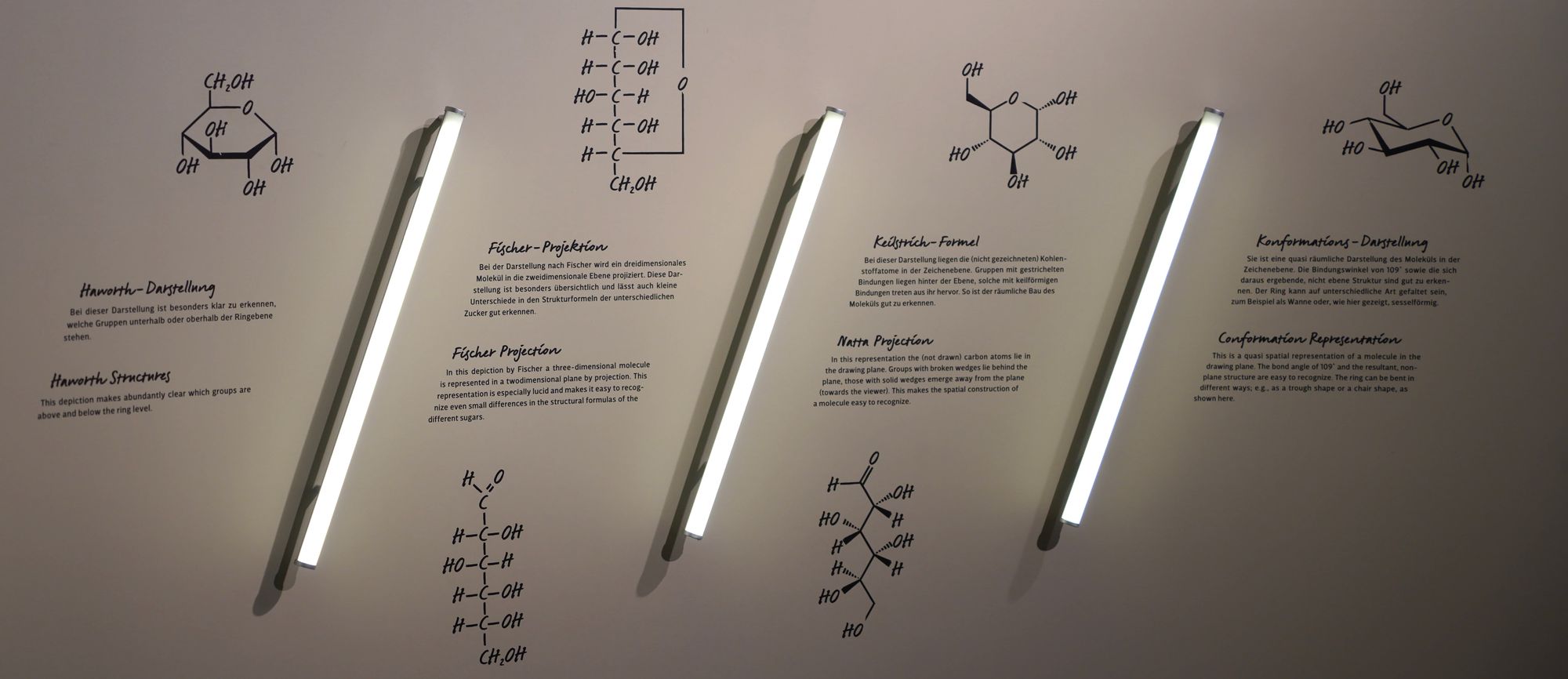

Seeing the spatial structure of monosaccharides in an ordinary exhibition hall was quite surprising. After all, the fact that sugar forms a six-membered ring structure in aqueous solution, rather than simply being an aldehyde based on its molecular formula, already exceeds general knowledge. The detailed explanation of different ways to represent spatial structure seemed like a page pulled out of a basic organic chemistry textbook. It reminded me of the peculiar pleasure of secretly reading university textbooks during high school class time. However, most visitors probably had no particular reaction to this content. What was the purpose of presenting these exhibits? As a museum, it is natural to design exhibitions targeting specific audiences. However, the personal motives of the exhibition organizers to convey their thoughts are inevitably present as well.

As a personal blog that doesn't receive public funds, this place is probably my archive for storing weird personal thoughts and hallucinations. Bear with me.